Blockchain protocol upgrades

The Internet Computer blockchain is governed by the Network Nervous System (NNS), its algorithmic governance system. One of the many duties of the NNS is to orchestrate upgrades of the Internet Computer to a new protocol version when the community has adopted an upgrade proposal. Making upgrades to any blockchain requires solutions to several challenging problems posed by the nature of decentralized systems including how to allow arbitrary changes to the protocol, preserve state of all canister smart contracts, minimize downtime, and roll out upgrades autonomously.

Any software needs to be updated on a regular basis to stay competitive in the market. This could be to fix bugs, add new features, change the algorithms, change the underlying technology, etc. Blockchain protocols are no different. As a community, we keep learning better ways to solve our problems and would like to upgrade our blockchain protocols accordingly. For example, Ethereum had “The Merge” upgrade, which upgraded their protocol from Proof of Work to Proof of Stake. Bitcoin had the “Taproot” upgrade, which improved their signature verification.

While upgrading a blockchain protocol is extremely crucial for its success, most blockchains including Bitcoin and Ethereum are not designed to do so easily and frequently. This is primarily because blockchains are not controlled by a single authority. Every upgrade proposal has to be evaluated by the community. However, the community is usually split on the proposals. There is no quick and formal framework to finalize the decisions and build new features. Upgrades to the protocol potentially cause a fork in the network. As a result, upgrading a blockchain protocol could take years of joint effort by the community. Ethereum went through only 18 protocol upgrades in a 7.5 year time span.

The Internet Computer is a unique blockchain that is designed to be easily upgradeable with a minimal user-perceived downtime and without any forks while still requiring consensus by the community for each upgrade. Within 1.5 years after genesis, the Internet Computer has upgraded many times, adding crucial features such as deterministic time slicing, Bitcoin integration, Service Nervous System (SNS), HTTPS outcalls, chain-key ECDSA signatures (based on threshold ECDSA), increased stable memory, etc.

The “protocol upgrades” feature is designed with the following goals: (1) Allow arbitrary changes to the Internet Computer Protocol; (2) Preserve the state between upgrades; (3) Minimize downtime; (4) Roll out upgrades autonomously.

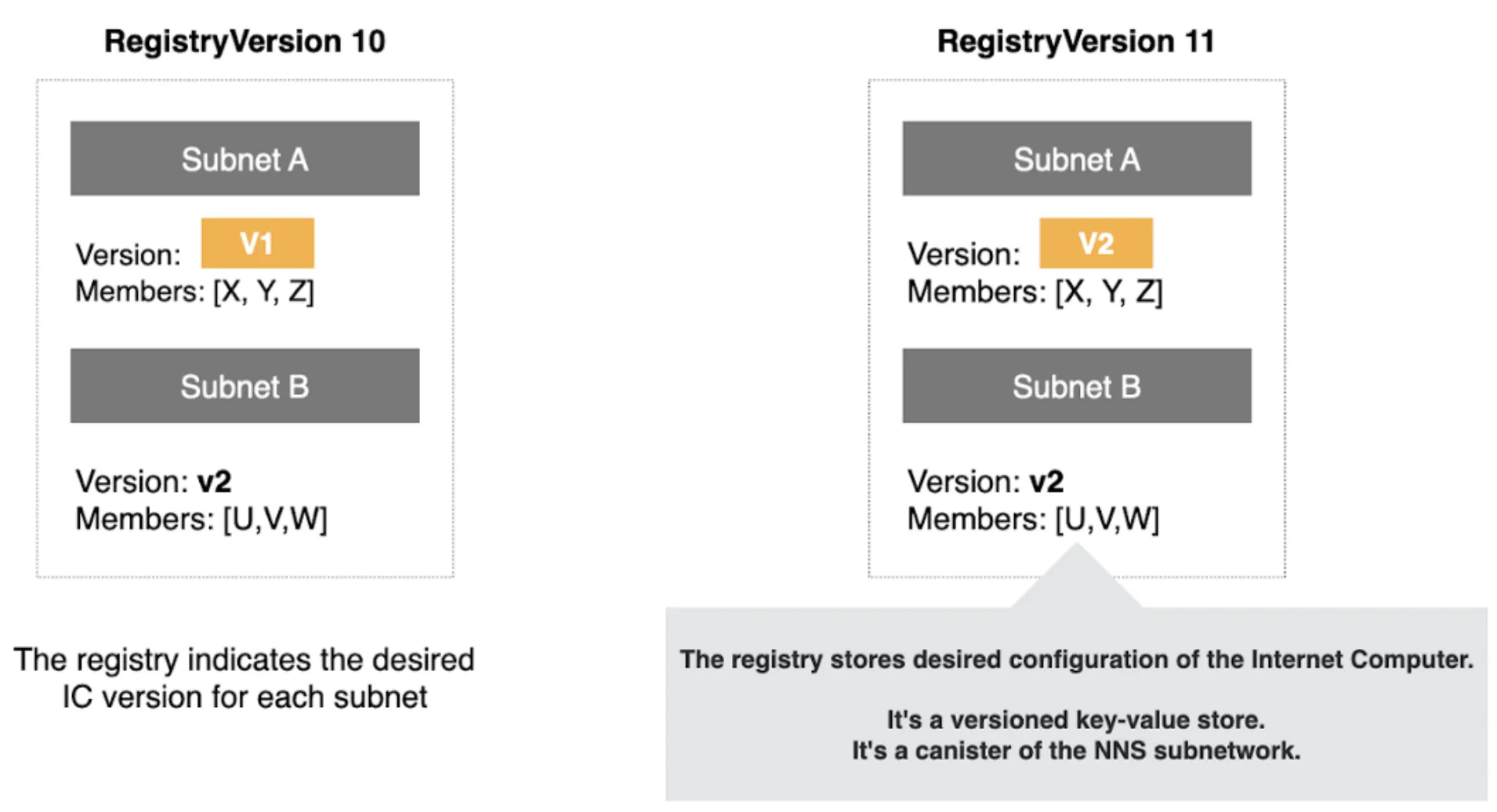

Protocol upgrades are made feasible due to the blockchain governance system called Network Nervous System (NNS). In the NNS, there is a component called “registry”, which stores all the configuration of the Internet Computer. A versioning system is implemented for the configuration. Each mutation to the configuration shows up as a new version in the registry. The registry has a record for each subnet which includes a replica version, list of nodes in the subnet, cryptographic key material to be used by the subnet, etc. Note that the registry stores the desired configuration. The subnets might actually be running one of the older configurations.

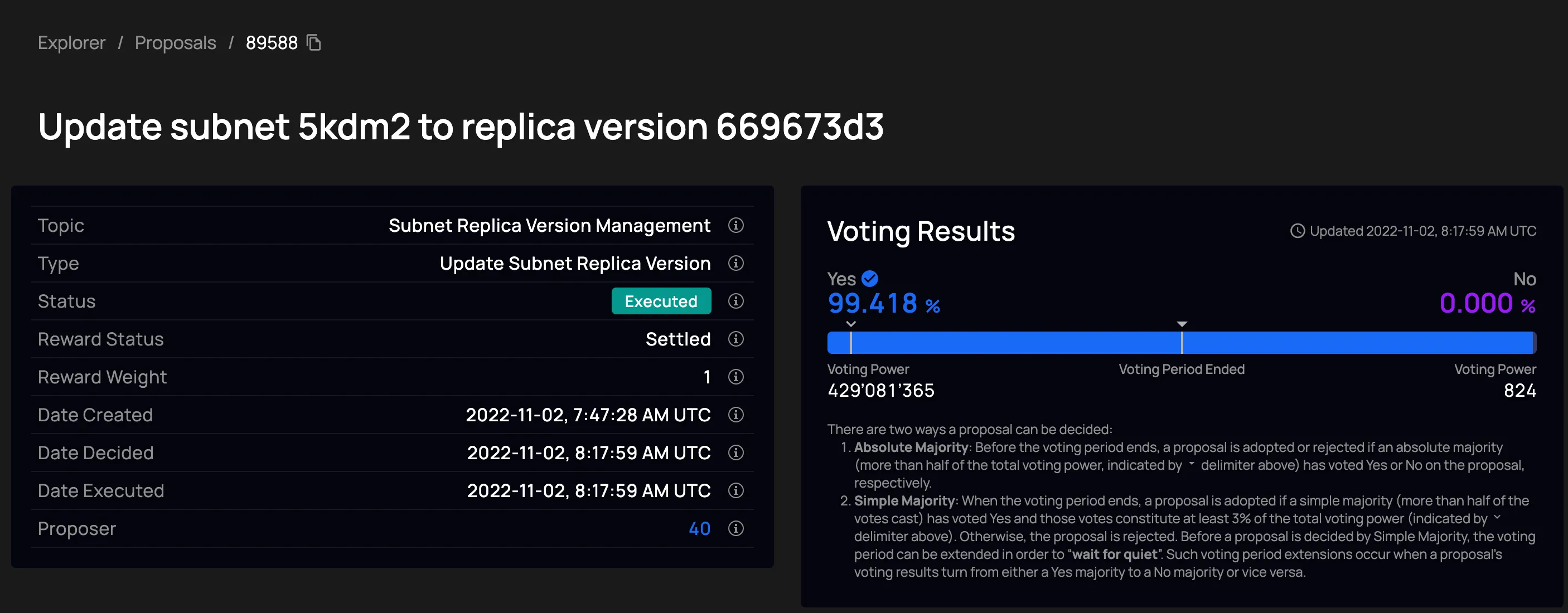

To trigger a protocol upgrade, one has to submit a proposal in the NNS to change the configuration of the registry. The proposal can be voted by anyone who staked their ICP tokens. If a majority of voters accept the proposal, then the registry is changed accordingly.

We now describe how a change in the registry component upgrades the Internet Computer. Protocol upgrades are done on a per-subnet basis. Each subnet is run by many nodes. Each node runs 2 processes — (1) the Replica and (2) the Orchestrator. The replica consists of the 4-layer software stack that maintains the blockchain. The orchestrator downloads and manages the replica software. The orchestrator regularly queries the NNS registry for any updates. If there is a new registry version, the orchestrator downloads the corresponding change and informs the replica about it.

In each consensus round, one of the nodes in the subnet (called the block maker) proposes a block. In every block, the block maker includes the latest registry version it downloaded from the registry canister. Other nodes notarize the block only when they have the referenced registry available.

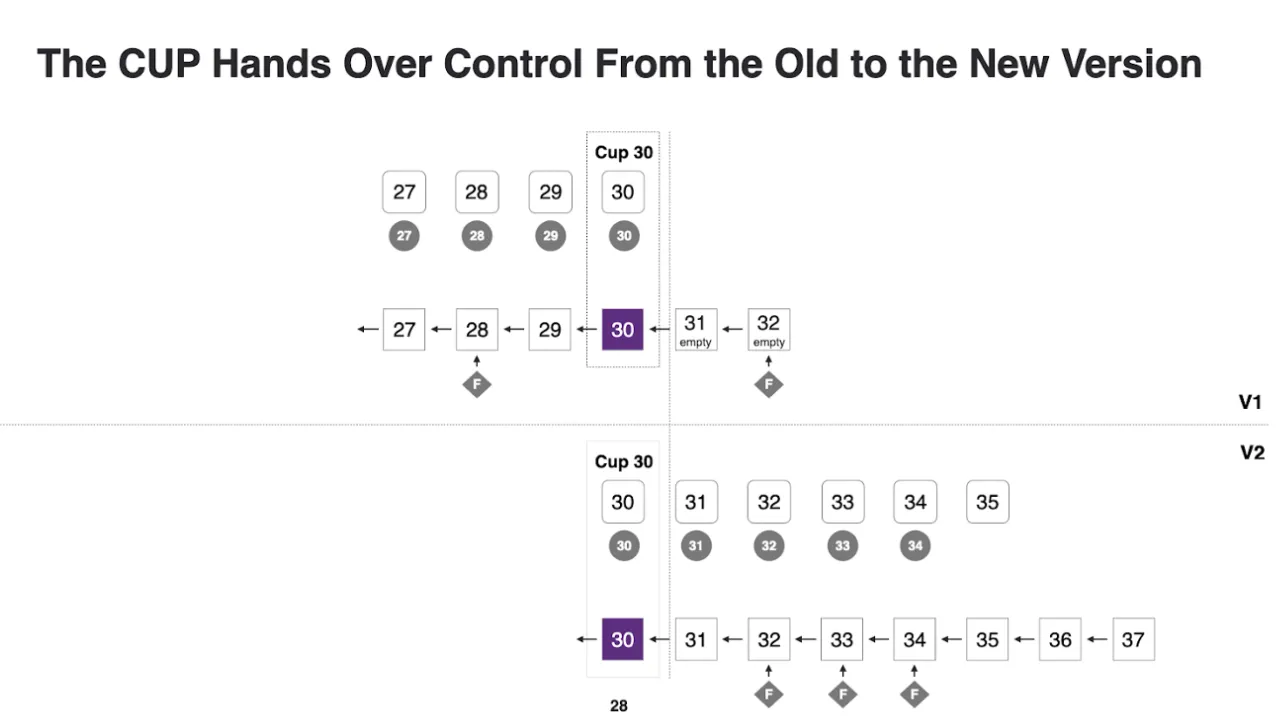

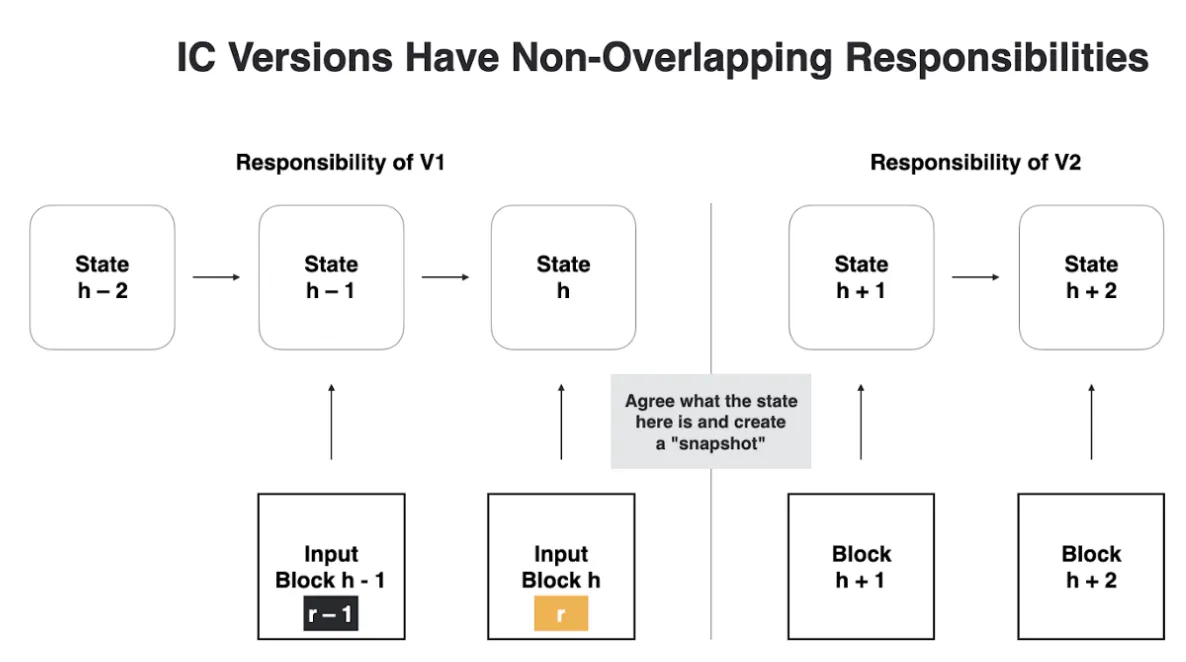

If the subnet record in the registry indicates a replica version change, the orchestrator downloads the corresponding software. After all the nodes in the subnet agree upon the latest registry version via consensus, the obvious next step is to switch to the new version. To avoid forks, it is crucial that all the nodes coordinate and switch their version at the same block height. To achieve this, the consensus protocol is divided into epochs. Each epoch is a few hundred consensus rounds (can be configured in the registry). Throughout an epoch, all the replicas in the subnet run the same Replica version, even if a newer Replica version is found in the registry and included in the blocks. Protocol upgrades happen only at the epoch boundaries.

The first block in each epoch is a summary block, which consists of the configuration information (including registry version and cryptographic key material) that will be used during the epoch. The summary block of epoch x specifies both the registry version to be used throughout epoch x, and the registry version to be used throughout epoch x+1. Therefore, all the nodes agree on what registry version to use for an epoch long before the epoch starts.

Suppose a protocol upgrade of the subnet is supposed to be done at the beginning of epoch x indicated by a replica version change in the registry version the nodes agreed on. A blockmaker first proposes the summary block. The nodes then stop processing any new messages, but produce a series of empty blocks until the summary block is finalized, executed and the complete replicated state is certified. Then, all the nodes create a catch up package (CUP), which contains the relevant information that needs to be transferred from the old replica software to the new replica software. The CUP gives enough context for the new replica software to resume consensus. The replicas send the CUP to the orchestrator. The orchestrator runs the new replica software with the CUP as input. Section 8 of the whitepaper describes the contents of the summary block and catch up package in detail.